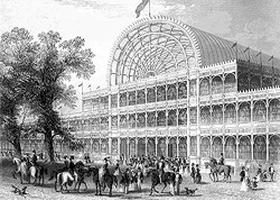

The Crystal Palace, London, 1851

While the relationship between architecture and the capitalist marketplace can be traced throughout the years, its most profound manifestation occurred in nineteenth century England during “the golden age of Victorian capitalism.”1 The Industrial Revolution saw the birth of a new consumer culture, and new architectural forms developed in response. Two forms that are most notably linked with the increase in economic activity and the growth of a consumer culture are the exhibit hall and the railway terminal. The Crystal Palace and St. Pancras Station, both in London, illustrate economic growth and consumerism through both their physical construction and intended use.

The Crystal Palace, “the largest, most celebrated, and remembered Victorian building of iron-and-glass construction,”2 was built by John Paxton to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. In his design Paxton seized upon the strength of iron trusses and supports to create a maximum interior area using a minimal amount of materials. Paxton's design drew upon the latest technology to create a large open building that increased square footage and capacity while reducing material costs. The use of prefabricated components and standardized forms allowed for quick and cheap construction, the likes of which were new and modern.3 Paxton made no attempt to hide the construction of the Crystal Palace , instead embracing the material as emblematic of progress and industrialization. James Stevens Curl, author of Victorian Architecture, states that “the Crystal Palace became the precedent for a great number of large temporary exhibition buildings… involving mass-produced factory-made components.”4

The Crystal Palace, “the largest, most celebrated, and remembered Victorian building of iron-and-glass construction,”2 was built by John Paxton to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. In his design Paxton seized upon the strength of iron trusses and supports to create a maximum interior area using a minimal amount of materials. Paxton's design drew upon the latest technology to create a large open building that increased square footage and capacity while reducing material costs. The use of prefabricated components and standardized forms allowed for quick and cheap construction, the likes of which were new and modern.3 Paxton made no attempt to hide the construction of the Crystal Palace , instead embracing the material as emblematic of progress and industrialization. James Stevens Curl, author of Victorian Architecture, states that “the Crystal Palace became the precedent for a great number of large temporary exhibition buildings… involving mass-produced factory-made components.”4

Interior view of the Crystal Palace.

The Crystal Palace showcased over 100,000 products from 14,000 exhibitors around the world.5 When considering the scope of the Exhibit, Prince Albert marveled at how. “the products of all quarters of the globe are placed at our disposal… and the powers of production are entrusted to the stimulus of competition and capital.”6 The Great Exhibition's goal was to showcase products to potential buyers with the Crystal Palace as its focal point – a cathedral of capitalism beckoning to the faithful consumer. The overwhelming and impressive nature of both the exhibits and exhibit hall played upon the consumer's wants, encouraging what Marx would call a “fetishism of commodities.” In his 1851 study of labor and commerce, William Felkin observed how “the Great Exhibition taught British men and women to want things and to buy things, new things and better things.”7 Indeed, Felkin was right; over six million visitors wound their way through the Crystal Palace generating a £186,000 profit for the festival and making the Great Exhibition a success.8

The Great Exhibition stood for all that was new and progressive, with the Crystal Palace as a symbol of Britain's economic supremacy. The staging of such an enormous event required the mobilization of both people and goods, including construction materials for the exhibition hall. England 's railway system expanded to accommodate the increase in passengers and the shipment of goods, lacing the countryside with its iron tracks. .As symbols of progress, movement, and change, railway tracks and terminals “changed not only building technology but also the very fabric of society.”9

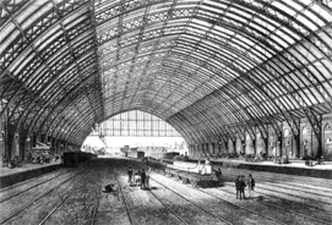

The notion of the railroad is a product of industrialization, and it is fitting that the railway terminus be a monument to the capitalistic growth which led to its formation. One such structure is London 's St. Pancras Station, another iron and glass creation symbolic of the economic impact upon the architecture of the 19th century. Built by engineer William Henry Barlow in 1873 and influenced by the design and construction of the Crystal Palace, St. Pancras utilized iron construction and prefabricated components.10 Like the other glass and iron terminals that dotted the landscape, St. Pancras was a physical manifestation of commerce and industry. Belching with steam and bustling with goods and people, the railway station's formation and construction were direct results of England 's industrialization and economic growth.

The Great Exhibition stood for all that was new and progressive, with the Crystal Palace as a symbol of Britain's economic supremacy. The staging of such an enormous event required the mobilization of both people and goods, including construction materials for the exhibition hall. England 's railway system expanded to accommodate the increase in passengers and the shipment of goods, lacing the countryside with its iron tracks. .As symbols of progress, movement, and change, railway tracks and terminals “changed not only building technology but also the very fabric of society.”9

The notion of the railroad is a product of industrialization, and it is fitting that the railway terminus be a monument to the capitalistic growth which led to its formation. One such structure is London 's St. Pancras Station, another iron and glass creation symbolic of the economic impact upon the architecture of the 19th century. Built by engineer William Henry Barlow in 1873 and influenced by the design and construction of the Crystal Palace, St. Pancras utilized iron construction and prefabricated components.10 Like the other glass and iron terminals that dotted the landscape, St. Pancras was a physical manifestation of commerce and industry. Belching with steam and bustling with goods and people, the railway station's formation and construction were direct results of England 's industrialization and economic growth.

The interior of St. Pancras Station, London

Rail travel was useful in bringing people to centers of commerce as seen in its promotion as an inexpensive means of attending the Great Exhibition.11 Author Asa Briggs notes that “St. Pancras was a commercial rather than a civic building and the mid Victorian achievement was above all else industrial and commercial.”12 The station's large interior space was capable of accommodating several trains at once, allowing for an increase in arrivals and departures. By its very nature the railway system speaks of economic progress through the shipment of goods over a large area. The fabrication of architectural components was no longer a localized affair; factories specializing in the mass-production of building materials shipped their products via railway to building sites across the country, enabling the erection of modern structures.

Both the exhibition hall and the railway station are architectural forms intimately linked with economic progress, consumer growth and capitalist aspirations of the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace and St. Pancras Station are excellent representations of their respective building types. Made of glass and iron, new building materials of the industrialized age, their construction and use are emblematic of the economic climate in the 19th century. Whether displaying products for consumption or moving people and goods, both the Crystal Palace and St. Pancras Station “represent the economic values of the new capitalist society.”13

Both the exhibition hall and the railway station are architectural forms intimately linked with economic progress, consumer growth and capitalist aspirations of the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace and St. Pancras Station are excellent representations of their respective building types. Made of glass and iron, new building materials of the industrialized age, their construction and use are emblematic of the economic climate in the 19th century. Whether displaying products for consumption or moving people and goods, both the Crystal Palace and St. Pancras Station “represent the economic values of the new capitalist society.”13

- Cowden, Morton H. “Early Marxist Views on British Labor, 1837-1917.” The Western Political Quarterly 16 no. 1 (March 1963): 34-52, pg 40.

- Curl, James Stevens. Victorian Architecture. Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1990, pg 205.

- Biddle, Gordon. Great Railway Stations of Britain: Their Architecture, Growth and Development. North Pomfret, VT: David & Charles, 1986, pg 103. The author states that “the new principle of prefabrication enabled ironwork to be erected cheaply and quickly.”

- Curl, pg 208.

- Auerbach, Jeffrey A. The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999, pg 91.

- H.R.H. Prince Albert. “The Exhibition of 1851” (speech, The Lord Mayor's Banquet, London, October 1849). Quoted in Pevsner, High Victorian Design: A Study of the Exhibits of 1851, 17.

- Auerbach, pg 121.

- Vickers, Graham. Key Moments in Architecture: The Evolution of the City. New York: Da Capo Press, 1999, pg 122.

- Pevsner, Nikloaus. High Victorian Design: A Study of the Exhibits of 1851. London: Architectural Press, 1951, pg 18.

- Curl, pg 210. The author states that “railway termini were influenced by the precedent of the Crystal Palace.”

- The promotional advertisement for the Midland Railway Company offered various classes of travel to accommodate all classes of travelers.

- Briggs, Asa. Review of St. Pancras Station by Jack Simmons. The English Historical Review 89 no. 350 (January 1974): 217.

- Norberg-Schultz, Christian. Meaning in Western Architecture. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1975, pg 328.